Prepared by Brother Jakes Homiak

International Rastafari Archives Project (IRAP), Alexandria, VA 22315, April 4, 2020

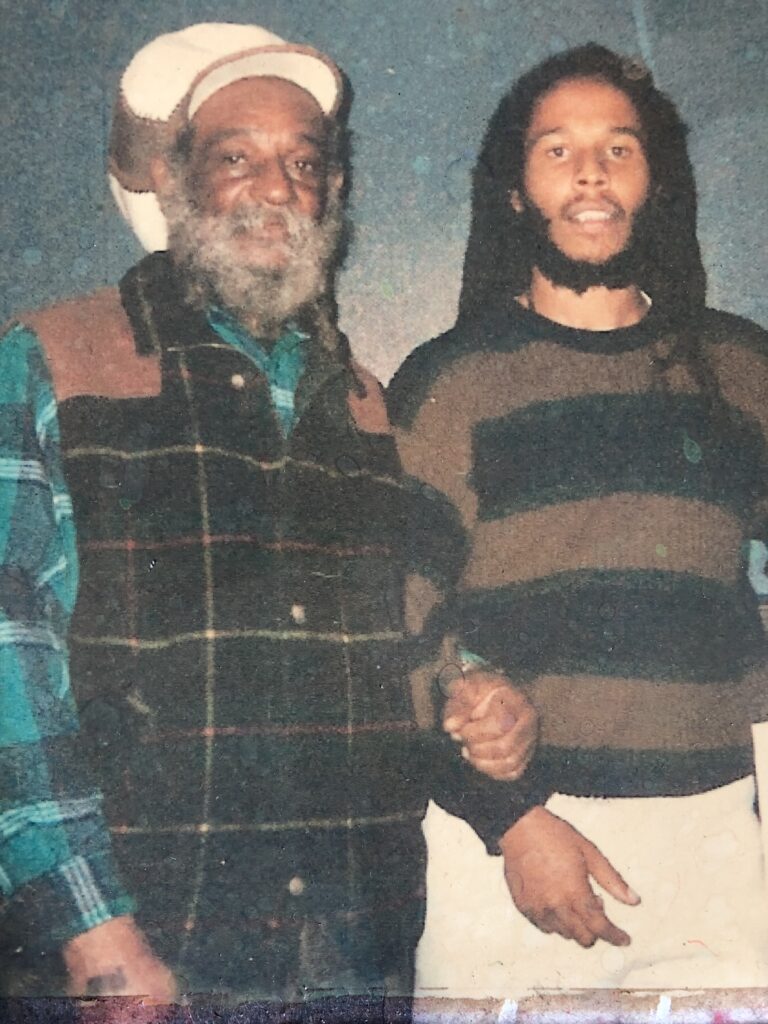

Ras Maurice Clarke (aka Maurice Fabian Clarke), birthed: ‘from Creation’; born Sep 27, 1938, 31 Pouyat Street, Jones Town; but christened in Kellits, Clarendon)

The Rastafari say that “JAH calls one from every family.” In his family, Ras Maurice Clarke was indeed that “ONE.” Born to Wilfred Patterson Clarke of Portland and Vernice Maude Robotham of Kellits, Clarendon on September 27, 1938 in Jones Town (Kingston), Ras Maurice came into the world during the tumultuous time of the all-island labor riots that rocked the Jamaica during that year and beyond.

The Camp-and-Yard Era of Rastafari.

As a schoolboy he attended Calabar in Kingston but would leave school around thirteen years of age, not unusual for a young boy at the time. By then, he was drawn by Ras Tafari to the world beyond his mother’s home. He ran away from home at the age of thirteen only to be ‘captured’ by his father and returned. He didn’t stay long. By fourteen he had enrolled informally in the ‘University of Adversity’, returning to a ‘grounding spot’ he had begun to frequent on Paradise Street in East Kingston where Rastafari brethren and fisherman regularly gathered. At first, he slept under an overturned fishing boat near the shore. Later he constructed a rude ‘tatu’ of slab boards and zinc as his gates. By the age of 15 he was turning dread and was picking up odd jobs with his brother Hadley who worked on the wharf, fished, and was later a pilot for Kingston harbor.

Irice’s first decades as a young Rastafari spanned the legendary ‘camp-and-yard’ era of the movement, roughly the late 1940s through the early 1970s. By the time his sojourn at Paradise Street began, the gravitational center of the movement had shifted from rural sites like Leonard Howell’s commune at Pinnacle in St. Catherine to the shanty towns and ghettoes in East and West Kingston. There, during the mid-1950s, Ras Irice began to gather other brethren of his age group and to acquire respect—both from his age-mates and Elders—as an intelligent and resourceful youth.

Attracted to the figure of His Imperial Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I and to the Pan-African ideas of Garvey and the Rastafari, young Irice worked to compile his own ‘true-brary’ (library) within his tatu at Paradise Street. His holdings were entirely books and magazines that held information about Ethiopia and Africa. Marking that period was the Rastafari support of the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya. Irice remembers the street marches organized by members of the Youth Black Faith supporting the Mau Mau in 1953 and 1954 along with militant Rastafari like Ras Sam Brown who—along with his group on Foreshore Road, came to be known as “Mau Mau” during that time. Ras Irice’s interests in the African connection was further spurred by the visit of Liberian President William Tubman in 1954. He recalls, “I saw him [President Tubman] coming up King Street from Victoria Pier in a convertible and there was a big crowd around Parish Church off Parade. It was di talk of di town. Rasta look ‘pon ‘im [Tubman] like Marcus Garvey and say, “Marcus Garvey dat! Him nah dead!”

At Paradise Street, Irice was regularly in touch with a number of the foundational members of the Nyahbinghi congregation. These individuals included Bongo Rocky, who would ‘pass through’ on his way to visit his spars in McGregor Gully. Bongo Spence, an EWF bredrin linked closely with Mortimo Planno and Brothers Filmore Alvaranga and Douglas Mack, both part of Count Ozzie’s group at Rennox Lodge, frequently ‘passed through.’ All were also regular visitors at Paradise Street. As Irice puts it today, “I come into Rastafari as an ‘adult’. I didn’t keep no man’s company—dem keep I company ‘cause I was a ‘reader’ (one who was widely read) who can reason wid any man. I read African Opinion and Africa Challenge, magazines I get from visiting Dudley Thompson’s office [Duke Street] when ‘im come back from Africa; and groundings with Brother Lok-I who ran the Addis Ababa Book Store on King Street.[1] Mi could reason wid any elder in Back ‘o Wall dem time.” Ras Irice’s interest in reaching out to individuals like Dudley Thompson and others beyond the boundaries of the movement would shape the trajectory of his career in Rastafari as it unfolded over the next six decades.

The I-gelic House and Ital Ites.

By 1958, Ras Irice had become a young ‘camp master’, establishing the ‘I-gelic House’ camp in Wareika Hills. This camp would be characterized by the austere Ital ‘all-male’ trod that he had initially embraced while at Paradise Street. Those who gathered on the hill with him included Iston-man, Bongo Tawney, Ras Headfull, Ras Crucy, Bulla-Rim, Ras Marcus Reid, Food-I, Z-anda (Alexander) and Freddie-man.[2] Other regular visitors included Stove, Bongo Time, Ras Daggo, Dizzy Johnny (the trombonist for the Skattelites), Ras Milo, Sekkle-man, and Ras Mosey. A number of these individuals—most notably Bongo Time, Bongo Tawney, Ras Headful and Ras Marcus—would go on to become leading figures in the Nyahbinghi House locally and beyond. Even though the camp was a man-sight/site in those times, a few sistren did occasionally ‘pass through’ including Margaruita Mafoo, the partner of the legendary Don Drummond, and Sister Ma Yarna (now a matriarch living in Bermuda).

Members of the I-gelic House were all intensely zealous young Dreadlocks who were determined to publicly witness to the faith of Rastafari. They wore crocus bags, walked barefoot, rejected flesh and leather in all forms (including the use of drums), and embraced a combination of raw food (sea moss, raw coconut, scotch bonnet peppers) and stewed Ital food laced liberally with I-ppa (scotch bonnet peppers) with as many as twenty in a pot. Theirs was the real pepper pot! They innovated the most austere version of Nyahbinghi livity in all aspects of their lives—renouncing everything ‘from shop’ and rejecting ‘fleshiness’ not only in their food, but in all forms including wearing leather belts and shoes and even rejecting drums (headed with the skins of dead animals) to accompany their chants. Their rejection of the flesh extended to practices of celibacy for the period of the trod over several years. Dressed in crocus bags—which they called ‘higes knots’—they walked the burning hot asphalt streets of Kingston barefoot with their rods and staffs like Old Testament prophets. At the time, ‘carrying [wearing] locks’ was sufficient to disqualify one for conveyance on public transportation. Needless to say, they were doubly barred.

Inasmuch as Dreadlocks were typically denied access to public transportation during this period, Irice and his brethren would think nothing of walking across much of the island—to Montego Bay, Trelawney, Ochos Rios or other sites—to visit other brethren to attend groundations. Ras Irice remembers many trods from Kington to various parts of rural Jamaica or urban Jamaica—all barefoot. Once outside the urban precincts of Kingston on these trods, members had to be careful not to come under surveillance by the constabulary of whatever town or district they might be passing through. He recalls, for example, walking from Kingston to Chalky Hill, St. Ann with Dizzy Johnny, Iston man and Headfull to visit Justin Hinds. He notes, however, that these forays out into the countryside were fraught in terms of relations with the local constabulary. “Dem time if police find you ‘walking abroad without any means of explanation,’ jail you a guh!” Hence, as young dreadlocks their ears became attuned to distinguishing the particular pitch and wine of a police jeep’s gears. Escaping detection typically meant walking at night, listening for oncoming vehicles, and scuttling through the back yards or plots of villagers or townspeople. At times, they were apprehended and did go to jail, including on their walk to Chalky Hill. Long story short, this was a time when it took real courage to live as a Dreadlocks Rasta; a time when the Jamaican state declined to extend to the Rastafari even the minimal recognitions of citizenship. None of this would deter Ras Irice. In fact, he proudly declares that during this period he had 43 outstanding bench warrants for his arrest and never once held a sentence.

Ras Irice and other members of the I-gelic House were notable cultural innovators. They brought forward the distinctive sound known as “Itesvar,” a speech code that featured remodeling English and patois words with the substitution of the sound “I.” Hence, the generation of utterances such as “I-yuncum I-yadda. I-yasta Yoolie I. I-n-I I-yanting Ises unto I-yack I-yadda, Haile Selassie I! (The Nyahbinghi [Bongo] Order is here! Ras Tafari! I-n-I are chanting Ises unto our Black Father, Haile Selassie the First!)[3]. Over the years, Itesvar would become entwined and contribute with other forms of what today often referred to as “Dread Talk” (see Homiak 1997).Their grounation sessions were also unique. Although living nearby above Count Ozzie’s camp at Rennock Lodge—one of the groups that innovated Nyahbinghi drumming rhythms—the Igelic House rejected the use of drums (due to their animal skins) and chanted acca pela in a register that foregrounded the sound “I” sung through a range of octaves. The frequent all-night sessions of chanting by the members of the I-gelic house did not go unnoticed by the residents below.

From the proximity of their camp in Wareika Hills to Rennox Lodge, the residence of Count Ozzie and his group at 56 Adastra Road, Ras Irice would ground frequently with that group, largely Combsomes, where he knew Brothers Alvaranga and Douglas Mack, Bluebeck, Bongo Bode and Ras Stove, among others. He recalls well when the 1961 Mission to Africa embarked and later gathering with Count Ozzie’s group to listen as letters from Alvarange and Mack on events associated with the Mission were read publicly to members of the community. Irice’s camp also opened a tract on the top of Wareika Hill leading to Brother Louva’s camp which was about two miles from them on another section of the hill. Brother Louva had been with Leonard Howell at Pinnacle and come to town in the early 1950s to establish himself on the hill (see D. Mack 1999:62).

In late 1960—in the aftermath of the so-called Henry Affair—the Igelic House encampment was raided (the first of three raids) by a detachment of police led by Superintendent Fullerton and captain David Simpson. Six brethren on the hill, including Ras Headfull, Ras Marcus, and Bongo Tawney, were arrested. By chance, Ras Irice escaped because he had gone to the ‘bush toilet’ just as the raid came down upon other members. The raid initiated a period during which Irice became—as he put it—”an up-and-down-person” moving back and forth from town to various parts of the country. For the two years before Emperor Haile Selassie I’s visit, Irice kept a cultivation in Button Bay, St. Thomas next to the Nyahbinghi Elder Bongo Ezekiel and he also lived for a time with Papa Lee in Mt. Moriah, St. Ann. This was a period of back-and-forth between St. Thomas and Back ‘o Wall.

The Wareika Hill-Back ‘o Wall Nexus.

Members of the Igelic House were among a number of groups of younger Rastafari who, through their visiting patters, linked the shanti towns of Back ‘o Wall, Ackee Walk, the Dungle, Salt Lane, Trench Town, Shanti Town (Foreshore Road), Moonlight City (Hunt’s Bay), McGregor Gully. All of these camps and yards, along with many other parts of the urban landscape, were networked together by personal ties between brethren and sisten as well as reciprocal visiting and hosting between camp members. For the Igelic House, however, Back ‘o Wall (and to a lesser extent Moonlight City), remained locales of special significance. Starting around 1959, Ras Irice and members of the Igelic House established an active pattern of visiting with brethren and sistren in these locales. Their group ‘trods’ from the East to the West were memorable for “dropping lightening and fiya” on every police station and church they passed on the way. As they established a presence in Back ‘o Wall, they brought their Ital traditions with them and transplanted them there among ones like Ras Ruppert, Leggs, Bongo Ozzie and others. By the early 1960s, Ras Irice had built his own tatu in Back ‘o Wall not far from the ‘court’ area known as Egypt and this began another gathering place for he and members of the Igelic House. Even though the Ital austerity of Irice and his group could have set up criteria for exclusivist forms of association, Irice and others ecumenical in their visiting patterns. This included periodically taking in the services of Prince Emmanuel and his congregation in Ackee Walk (54B Spanish Town Road), links to Mortimo Planno’s group in the Dungle and on Salt Lane, to Ras Sam Brown and Ras Shadrach and their groups along the Foreshore Road in what was known as “Shanti Town.”

Irice recalls that “It took skill fi live in Back ‘o Wall ‘cause di whole land was open land wha used as a dump. Truck jus’ dump all kinda garbage an ‘ting der. If we capture a spot, we just rake off dem tings—rake off di garbage an’ bury it. As I describe it was a dump…you have to be skillful to live a back a wall ‘cause it breed alot of ground lizard. Yuh know dem? Your floor is dirt, ya know…an’ you see one a dem come outta your floor. Dem have teeth an’ gwaan bad. If you use cardboard inna your gates.. roach an ting lay egg inna dat. When it rain it put out roach ta grannie bulb! So, if you hab a pot going you have to quick cover it and defend it. An’ you haffa burn fire in der and smoke dem out. But wi Irie still inna wi crocus bag an’ free inna wiself.”

The late 1950s and early 1960s were challenging times for the Rastafari as an acutely peripheralized community. These years were ‘hot times’ for brethren and sistren given the agitation for repatriation raised by Prince Emmanuel’s 1958 all-island Convention. This was followed by the Coronation Market Riot in May of 1959 that spilled into Back ‘o Wall—leading to the arrest of 57 Rastafari and the forcible trimming of a number of them—and later to the Henry Affair in 1960. Durin the Coronation Market Riot in May of 1957, Ras Irice barely escaped being trimmed as the riot spilled out into the adjacent areas. Standing on Spanish Town Road as the riot spilled into Back ‘o Wall, he witnessed one of his brethren, Bongo Ozzie (aka Keith Hoyes) being accosted by police who forcibly held him down and trimmed his full head of locks with the cutlas of a nearby ‘jelly’ vendor. Irice recalls that “He was at ‘im home premises—right in ‘im yard, and dem trim him with cutlass right there next to where ‘im grow ‘im callaloo. If mi never leave quck, mi inna problem too. To anybody dem see, Babylon [the police] dong ‘pon dem same time.”

Still moving back and forth from Back ‘o Wall to Wareika Hill, Irice and his group came under increasing pressure after the Henry Affair in June of 1960 when Henry’s son Ronald and other of his followers killed two members of the Royal Hampshire Regiment in the Red Hills. Complaints to the police from residents below the Igelic House camp became common by the summer of 1961. Their camp was raided by a contingent of over 200 policemen led by Superintendant Fullerton. Nine bredrin, including Ras Headfull, Bongo Tawney, Ras Marcus Ras Crucy and others were arrested in the raid—held on the basis of a herbs pipe that had been left in the croch of a small tree by their camp. When the police, producing the chalice, cheekily demanded to know, “What is this?” Bongo Tawney responded, “That is bird’s love!” Ras Irice was sparred apprehension and trail at the Sutton Street Court House because at the time of the raid he was in the bush and had slipped past the encircling police. None of this, however, deterred the zeal of the camp members.

Ras Irice would be in Back ‘o Wall when the news of the Coral Gardens massacre flashed across the island. He recalls that a number of Rastafari from the Montego Bay side walked across the island to seek refuge in Back ‘o Wall and that in the days and weeks around that event a number of Rasafari were caught on the streets and trimmed—not simply with cutlasses or scissors. They would be forcibly held down and had their locks ‘scraped off’ by the police with the razor-sharp edges of broken bottles. As he notes, “Yuh mus’ realize dat a lot of atrocity affect Rasta dem time dat never publish. I-n-I know di half has never been told even to this day!”

As noted, Irice had already seen President Tubman during his visit to Jamaica in 1954. By the late 1950s-early 1960s, he was an avaid Pan Africanist reading everything he could on Africa and the tide of independence that was sweeping the continent. This included periodic visits to Dudley Thompson’s law office to procure copies of The Ethiopian Observer and African Outlook. In 1962, Irice, Bongo Tawney and other members of their cohort met Michael Okpara in front of Coke Chapel. Okpara, the former Prermier of Eastern Nigeria under self-rule that began in 1959 prior to their independence was a Zikist and a member of his government at the time. In late 1963, after the assassination of President Kennedy, Ras Irice, Bongo Tawney and others greeted two unexpected visitors in Back ‘o Wall—South African singer Merriam Makeba and black activist Stokley Carmichael (aka Kwame Toure). Irice remembers that:

“They came through ‘Bump’–which is de gate to Back o’ Wall. Harry Belefonte was der in di midst…I feel it was him who did bring them as a person who have a sympathy fi Rasta…and like man say, ‘You haffa know who is Rasta ‘cause is de heart of de slum dem come. Dem come inna di heart of Back ‘o Wall. Where the gathering was…it was right beside Bongo Lloyd, doing his shoework and Bongo Allen and ‘im queen, near di courtyard where binghi keep. It was so much people so mi just stand up and listen. Dem wan know how it say with I-n-I—cause wi know dat wi is part of di same struggle like Sharpesville and Soweto, seen. It could be more den an hour or two dem deyah. After dat, some woman start cut dem hair like her [Makeba] and wear clothes like her—her dashiki blouse and skirt. That help di dashiki to come in.”

Visitation of the King.

By late 1963 it became widely known that Back ‘o Wall was slated for demolition by the JLP government. Near the end of that year Ras Irice relocated from his gates there and on the Wareika Hill to Button Bay, St. Thomas where he occupied a plot of land and farmed adjacent to Bongo Ezekiel and his queen. It was at Button Bay that he and Sister Cherry had their first child, a daughter. There, in late March of 1966, Irice heard the announcement on his transitor radio that His Majesty would be making a state visit to Jamaica in April. He promptly sold ‘Willie’, his donkey, to an ancient named Bongo Harry and set off for town where he took up residence with Leggs-man on Foreshore Road. Irice, Leggs, Tawney and a few other brethren were at Palisadoes airport on April 21, 1966 to greet His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I. Like many other brethren of his age cohort, this was an unforgettable day for Irice. After the landing of His Majesty’s plane, he recalls being among the crowd that rushed onto the tarmac to surround the plane:

“And then I run off a go run to the plane. And when I go out […] I never go against the plane. Cyaan bore in dere so. I was like about 45 feet or so from the plane. But my eyes could see everything properly and I see man’s chalice, I see smoke, I see all a dese kinda tings, but His Majesty doan come offa di plane yet. […] Everyone interest is to see His Majesty come out of the plane. They were awaiting that vehicle that suppose to go up there and hitch up the steps. Then one time we see His Majesty—we SEE HIM—it must Him because him come out and go in back, seen? And then all of a sudden you see certain dignitaries gone up there like the Govenor General and Colonel Dunston Robinson, which is the Chief of Staff. […] And certain dignitaries I wouldn’t know by name.

And I remember when Mortimo Planno is going up there to deal with the crowd. But in my estimation, Mortimo Planno has a connection in him circle…there’s an Ethiopian ambassador for Trinidad, Jamaica and maybe somewhere else. That one ambassador cover those area and he often time visit Jamaica…and Mortimo Planno may have some connection [to him]. So I am thinking maybe the ambassador did fetch him and something did organize […] From where I was and viewed the situation, him couldn’t be too far from there so.[…] So Planno gone up there and we watch that…and the big hooray and all a dem ‘ting dere. So His Majesty come off and waive to everyone and create a big nice joy. And then HIM coming down to him vehicle…Believe you me, Jakes, I is looking on His Majesty same as how I see him ‘pon the portrait, yuh know! Same way I!!!

The moment of that sighting, Ras Irice recalls, became his ‘graduation in Rastafari.’ From that moment forward, nothing could shake his faith in His Imperial Majesty.

After Back ‘o Wall was destroyed in August of 1966, Ras Irice took up residence first with Leggs man on Foreshore Road and then in Trench Town near West Road. There he came to know a young Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, among others who would go on a reggae stars. He was an ‘herbs man’ during those times and a youth would frequently come from Bob’s yard requesting that Ras Irice “send up a good draw of herbs” to aid their lyrical mediations. The decades of the 1960s and 1970s were ones during which he remained a faithful ‘binghi man. During those decades Irice and his peers were active in many of the early Nyahbinghi troddings to rural parishes—trodding from Mahoe Hill in Portland to Ras Daniel’s tabernacle in Freeman’s Hall, Trelawny, from Iyuncum P’s grounation in Back Pasture in St. Catherine to Pa-Ashanti’s binghi at Robbin’s Bay, St. Anns and from Bongo Ezekiel’s ‘binghi in Button Bay, St. Thomas to Iyah Vee’s in Little London, Westmoreland, among many others. Even after Ras Irice secured a position as beach manager for the Intercontinental Hotel in Ochios Rios (1974-79), he continued to trod ‘binghi—often using the hotel’s van to ferry bredrin and sistren across parts of the island to various venues.

Father Irice Outernationally.

This writer met Ras Irice in November of 1980 at the Golden Jubilee Nyahbinghi celebration at Angel Ites, Bog Walk, St. Catherine. As it happened on that occasion, I gave him and a next bredrin a ride back into Kingston one evening and shared my information with him. We would renew our association nearly eight years when he telephoned me shortly after the first delegation of Nyahbinghi Elders to the U.S. landed in New York City. Through the offices of the Smithsonian, I had secured the visas for the Elders to travel and Ras Irice was insisting to me that he needed, however belatedly, to be part of that mission. A few phone calls and several days later he would arrive in Baltimore to fit in which the delegation. The rest, as they say, is history.

The following summer another delegation of Nyahbinghi Elders would be invited to perform at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival—without, as it turned out—any official support from the Institution. Undetered, Ras Irice would mobilize members of the Baltimore Rastafari community to provide housing and transportation for the participants who included Bongo Tawney and Sister Pam, Sister Ina, Mama Bubbles, Bongo Pidow, Bongo Shephan, Ras Headfull, Bongo Bigga, and Baba Marcus. Suffice it to say that Ras Irice emerged as a charismatic personality at the Folklife Festival, first having gained the confidence of the festival administrators who commissioned him to construct the dancing bode for the Jamaican participants. During the festival he ranged far and wide across its venues with his striking bifurcated “Kongo Knots” trailing nearly to the ground, being engaged by festival-goers and reasoning with Rastafari brethren and sistren many of whom had traveled long distances to see the Elders. After a successful run at the Foklife Festival—where the Elders were featured on the final day in an impromptu ceremony with the paramount King of Ghana’s Ga peoples and his entourage—the Elders went on to be featured at Reggaefest ’89. During that same, Ras Irice organized travel of the group to Chicago where they participated in the annual Bob Marley Festival and re-connected with Brother Gabriel Diaz, an Elder who came intro Rasta in the mid-1940s and who was part of Mortimo Planno’s circle.

In the years immediately following Ras Irice would participate in others significant public program. These included “Beats of the Heart/Rhythms of Resistance” at the American Museum of Natural History in New York (May 1990) which included Ras Michael (Sons of Negus), Pa-Jack Hewitt, Bongo Tawney, Pidow, Bigga and Shephan, Ras Sydney and Mama Bubbles and Sister Ina and “The Lion and the Lamb: Reasonings of Rastafari Livity” organized by the Smithsonian Anacostia Museum (1991) which included Ras Sam Brown and others from above. In 1992 he was instrumental in organizing a number of these same Elders and other local community members to perform at the headquarters of the Organization of American States (OAS) in D.C. and in 1994 he was a figure featured in Anacostia Museum’s exhibition entitled “The Black Mosaic” which celebrated the diversity of Black Diaspora cultures in the greater Washington D.C. area.

If Irice could be called a “camp master” in his earlier years in Jamaican, he would come to serve as a community organizer here in the U.S. Since 1989, it is fair to say that he has been on point for many, if not most, of the community celebrations in Washignton, D.C. Much of his work has gone to supporting the links that have developed between Rastafari in the Eastern U.S. over the past two plus decades. This not only includes his participation in formal public programs like those noted above, but his work in maintaining a broad social network of contacts across the U.S., the Caribbean and beyond.

In 1998 Ras Irice presided over the Washington, D.C. Nyahbinghi House on 10th Street, N.W. along with Pa-Jack Hewitt, an original member of Ras Michael and the Sons of Negus. That venue would not only host a number of events and visitors from other metropoles on the Eastern seaboard, it would be a teaching venue for local younger brethren and sistren “coming up” in Fari, including members of Howard University’s Caribbean Students Assocation. In 2001 Irice would be married to Sister Danita by a local priest of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and in his role as a leading light within the community he would go on to become the first President of the Iniversal Development of Rastafari (IDOR) in 2004. (He served from 2004 to 2012.)

During 2004 he would be involved in organizing for the 50th anniversary celebration of Emperor Haile Selassie I’s visit to the United States and he would be named to serve on the Smithsonian Advisory Committee for the planning of the Discovering Rastafari exhibition that was launched in November of 2007. During the entirety of the 1990s and 2000s, Ras Irice could always be found on the Nyahbinghi seal—often at rural venues in Brandywine, Maryland—keeping the duty for its duration. Father Irice, as he has come to be called by many, would go on to hold his post in IDOR until 2012. During the November 2 Coronation observance which IDOR held at the Ethiopian Embassy (and which was covered by IRIE FM), Father Irice was given IDOR’s lifetime achievement award. Today, despite being bedridden and dealing with his own medical challenges, Father Irice continues to serve as a “Living Book” for the community, both far and wide. And just as he proclaimed over 50 years ago when he personally sighted Emperor Haile Selassie I at Palisadoes, nothing can shake his faith in the King of Kings. In his words: “The full has never been told.” The same applies to the patriarch’s life-story.

Rise Up in Zion my Ancient—Yanting Ises around the Rainbow Circle Throne of His and Her Majesties. All Glory to the Most High Emperor Haile Selassie I in balance with Empress Menen Asfaw.

[1] Ras Lok-I’s parents ran a bakery and he provided for many of the bredrin with cornbread. The move from Paradise Street to Wareika Hill cut out fish entirely. Those days they would include cornbread in their diet. We never do baking for ourself on Wareika—except pudding, Iston would make potato and cassava pudding. Cornmeal pudding would get made with water and cane liquor—they had a cane press up on the hill. We gratter coconut, tek out di rich juce—the crème—mix up with cornmeal and vanilla and nutmeg and “bake it solid.” We have a yabba pot that is purposely for tea—tea boiling. The cane press—trees grow a certain kind a way—you have a tree like a mortar stick and you put between that with a zinc—it wasn’t a piece of hardware.

[2]A bredrin named Freddie-man lived at di food of di Hill and had a standpipe where Irice and other hill people go to catch water…carry a pail of water up on the hill. This was a thing much like Bobo Hill. Freddie man would later become Ras Irice’s link to Bongo Ezekiel, an elder who resided in Button Bay, St. Thomas where he, Iriz, would later sojourn.

[3] Scholars of Rastafari who are unfamiliar with the origins of this dialect have labeled it various as “Dread Talk” or “Rasta Talk”, neither of which designation does justice to the originators or the context of its origination.